BIOtech Now

Daniel Seaton

Later this morning, the House Energy and Commerce Committee will hold a hearing to examine the rampant abuse within the 340B drug discount program. The 340B program was created by Congress in 1992, with the support of the biopharmaceutical industry, to help uninsured and financially vulnerable patients gain access to affordable prescription drugs. As part of the law, drug manufacturers provide steep discounts on outpatient medicines and treatments to select hospitals and other health care entities — often referred to as safety-net providers, because they are supposed to be providing significant amounts of charitable care for the poor and uninsured. According to the Congressional Budget Office, these discounts from drug manufacturers average 49 percent off of the list price. Over the years, however, there have been growing concerns that the program has expanded well beyond true safety-net facilities and that patients may not be seeing the benefits of these generous discounts from drug companies.

We hope that today’s hearing will provide a fruitful discussion of the problems and potential solutions that currently exist in the 340B program. To that end, below are four questions to bear in mind regarding the program:

-

- A newly-released report from the Government Accountability Office confirms that abuse within the program is rampant, with contract pharmacies (includING pharmacies that are part of large publicly-traded chains) profiting handsomely from the provision of discounted 340B drugs to low-income, uninsured patients BEING SERVED BY 340B HEALTH CARE ENTITIES. Many of these patients are charged full price for their drugs, despite the DRUGS being sold by the drug manufacturer at an average 49 percent discount. In fact, 16 of the 28 340B hospitals examined in the GAO report did not pass along any 340B discount to their low-income, uninsured patients who fill prescriptions at their contract pharmacies. What’s more, these for-profit 340B contract pharmacies often earn profit margins of 15-20% on brand-name 340B prescriptions. That’s well in excess of industry norms, and all the more disturbing when one considers that these excess profits are taken directly from the pockets of the low-income, uninsured patients the program was created to help. How do we ensure that 340B program does not continue to allow large, publicly-traded pharmacies to directly profit at the expense of low-income patients, and that these needy patients are receiving the benefits of the drug companies’ steep discounts?

- According to a January report from the House Energy and Commerce Committee, audits performed by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the HHS agency charged with oversight of the 340B program, has found high levels of noncompliance with 340B program requirements by 340B covered entities. Specifically, the report found that “HRSA audits from FY 2012 to FY 2016 demonstrate that non-complying entities violate program requirements in a variety of different ways, including duplicate discounts, diversion to ineligible patients and facilities, incorrect database reporting, and violation of the Group Purchasing Organization (GPO) prohibition (if applicable).” In each of those years, over half of audited covered entities were found to have engaged in program requirement violations. Meanwhile, HRSA audits of drug manufacturers in the program have found no instances where manufacturers failed to comply with program requirements. Given these audit findings, what more can be done to ensure that 340B covered entities are complying with program requirements to prevent duplicate discounts, diversion of drugs to ineligible patients or facilities, incorrect reporting, and other program violations?

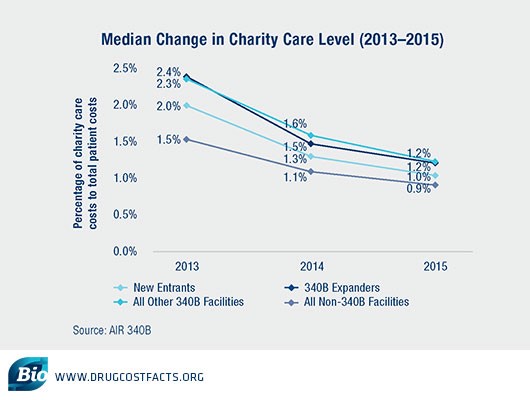

- 340B hospitals often claim that even if low-income and uninsured patients do not directly benefit from the 340B program in the form of lower out of pocket drug costs, they use program revenues to improve care for these patients in other ways.However, despite the staggering growth in the number of hospitals — and volume of purchases — made under the program, 340B hospitals have demonstrated a dramatic decline in charity care provided since 2013. Between 2013 and 2015, 340B disproportionate share hospital (DSH) facilities decreased charity care levels more substantially than non-340B DSH hospitals, raising questions about who is benefiting from 340B — patients or hospitals.

Meanwhile, a February 2018 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that “financial gains for hospitals have not been associated with clear evidence of expanded care or lower mortality among low-income patients.”Given these findings, what more can be done to ensure that 340B revenues are directly benefiting low-income and uninsured patients, rather than enabling hospitals to build new luxury facilities or increase executive pay?

Meanwhile, a February 2018 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that “financial gains for hospitals have not been associated with clear evidence of expanded care or lower mortality among low-income patients.”Given these findings, what more can be done to ensure that 340B revenues are directly benefiting low-income and uninsured patients, rather than enabling hospitals to build new luxury facilities or increase executive pay?

- Ample evidence now demonstrates that the 340B program provides perverse incentives for hospital to acquire community oncology clinics so that they may generate increased 340B revenues. This is problematic, because oncology care provided in a hospital setting is typically much more expensive – for both patients as well as public and private payers – than care provided in community oncology clinicals. As a May 2015 MedPAC report found:“Medicare spending grew faster among hospitals that participated in the 340B program for all five years than among hospitals that did not participate in the 340B program at any time during this period (19.1% per year vs. 13.9% per year, respectively).”While HHS took steps last year to rein in these perverse incentives by lowering reimbursement for 340B drugs in the Medicare program, the commercial insurance market still provides ample incentives for hospitals to acquire community oncology clinics, driving up costs for patients.111

-

- This trend was examined by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which recounted a patient who saw his out of pocket cost for a routine cancer care visit skyrocket from $20 to $212 after his clinic was acquired by a hospital. His insurance company’s cost for the same visit also more than doubled, jumping from $2735 to $5661. This was for the same treatment at the same office he visited every month – the only difference being that his clinic was now part of a large hospital network.

-

- What further steps can be taken so that the 340B program does not continue to drive lower-cost community oncology clinics, which are also often more conveniently located for patients, out of business?

While it’s clear that the 340B program suffers from many problems, bipartisan legislation introduced earlier this year would be an important first step in reforming the program. The 340B PAUSE Act, introduced by Reps. Larry Bucshon (R-IN) and Scott Peters (D-CA) would institute reporting requirements to help Congress and regulators better understand how the program is operating. It would also put in place a two-year moratorium on new hospital enrollment while Congress examines other needed reforms. A related bill was also introduced by Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA).

Another bill, the Ensuring the Value of the 340B Program Act of 2018, sponsored by Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA), would provide much-needed clarity for lawmakers and the public on how hospitals are profiting from the 340B Drug Discount Program.

While 340B hospitals tepidly claim to support “a thoughtful conversation about the transparency of the 340B program,” they have consistently opposed all efforts to introduce any accountability for how they use program savings. Let’s hope that Congress calls their bluff and takes action to reorient the program to promote patient health instead of hospital and pharmacy wealth.

Powered by WPeMatico